Fitness experts on strength training offer advice: what hinders and what promotes progress?

1. easy routes VS hard work

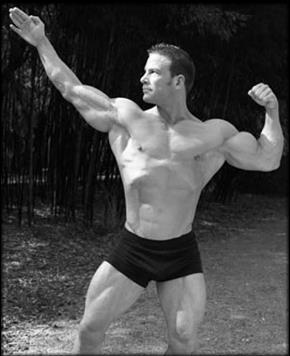

Clay Hite, chiropractor, trainer, nutritionist:

We always strive to avoid suffering and enjoy it (except for those for whom suffering is a pleasure – Zojnik translator’s note). However, to visibly transform our bodies, we have to put in a lot of effort with some discomfort at times.

For example, it is easy and simple to grab an oversweetened cereal bar as a source of carbohydrates; it is more difficult to make a cereal-bean meal yourself. In the first case, the brain is immediately rewarded, while in the second it has to be persuaded that there will be some benefit at some point in the future.

Easy – do leg bends on an exerciser, finishing the set when the ‘burning’ starts. Heavy – doing squats with the barbell on your back until you give up. Easy – to perform upper block pulling. It is hard to learn how to do real pull-ups. Easy – stomping on a treadmill. It’s hard to do VIT.

It’s easy to snack on fast food in the city; it’s hard to pack healthy snacks every day.

And yet, in order to change your figure for the better, you have to learn to tolerate discomfort and even physical pain, forget about instant ‘rewards’ and do exactly what will help you achieve your goals.

2. mindless entertainment VS healthy sleep

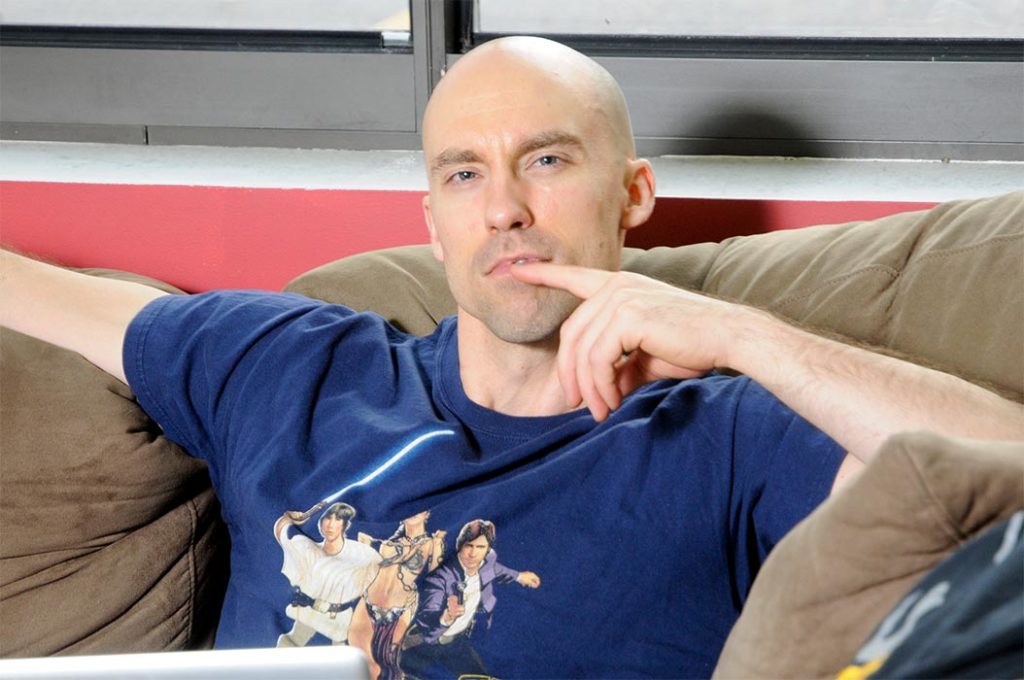

Tony Gentilcore, strength and fitness expert:

I turn into a grumpy old man who mutters the same thing endlessly on issues like this: if something (in fitness) has gone wrong, turn off your Netflix and go to bed.

The full benefits of exercise only come into play when you let your base-beaten body rest and recuperate. If you’re cutting into your nightly routine by binge-watching soap operas or arguing fiercely on forums with Daenerys2008, don’t expect anything good (from fitness).

Every time a client complains about lack of progress (or any desire to go to the gym), the first thing I ask about is sleep regime. Most often the problem is its violation, and helps the most simple solutions to the “evening ritual”: go to bed on time, turn off all the screens in advance, read a book, darken and cool the room, turn on a source of white noise, etc., etc. (read the text on how to get ready for bed in detail and with pictures on Zojnik).

If you’ve been working out at a standstill, try – before you buy extra sports nutrition and further bulk up/intensity – just start getting enough sleep.

3. trendy diets VS calorie counting

Eric Bach, strength and fitness expert:

Sometimes really workable and sensible eating systems become popular. But this is rarely the case; what usually erupts is a fashion for ‘super diets’ with strict restrictions of some nutrients and/or an excess of others. It’s hard to follow in the long run, and it’s not good for your health either. Instead of jumping from one trend to another, stick with the proven calorie-calculation method.

In our complex world, we can only manage what we can measure. Calorie counting ensures that you’re maintaining a surplus for muscle growth, or a deficit for shedding excess weight.

Whichever dieting system appeals to you, try counting your calorie intake for 60-90 days (at least once in your life). During this time you will learn to estimate how much useful or unnecessary energy is in certain portions of different foods. Further on, if you like, you can continue counting or switch to some diet. But the important understanding of the energy content will stay with you and certainly not interfere.

Have you added 2 tablespoons of olive oil to your salad? They have as many calories as a chicken breast. Snacked on peanut butter toast? And it has more calories than a pile of apples, banned by the new high-fat and fructose-free ‘hype’.

Calorie control has its drawbacks – it’s annoying, for example, to walk around all day with a kitchen scale, bills and notepad; but most great figures have been built that way, not by trendy diets.

4. egolifting VS real strength training

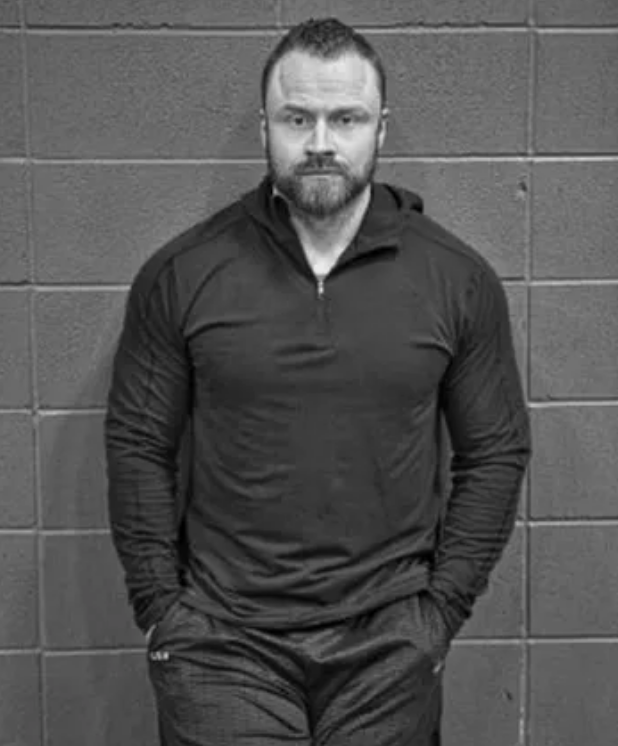

Andrew Heming, professor, strength coach:

The gyms are full of jocks trying to lift not weight but self-esteem. Quarter squats, biceps lifts with cheating (such that all muscle groups except the biceps work), bench press with insurance (in which the insurers have an easy stanova day).

Even normal weight-lifter sometimes gets hooked on ‘lifting’, achieving some success, for example, 150kg in bench press or 180kg in squat/drawbar. After that every time he visits he tries to break this record and get to the next round number.

- For example, a deadlift workout looks like this:

- Approach 1: 5 x 60 (kg)

- Approach 2: 3 x 100

- Grip 3: 2 x 140

- Approach 4: 1 x 165

- Grip 5: 1-2 x 180

In an ideal world he would constantly increase the 1RM, but in our real world he would overtrain, plateau, get injured. The intensity is too high, the volume is too low.

You go to the gym to gain strength, not to impress people around you with new records. Train hard, but not with excessive weights. Here’s an example of a normal strength training session:

- Warm-up sets:

- Approach 1: 5 x 60 (kg)

- Approach 2: 3 x 100

- Approach 3: 2 x 125

- Approach 4: 1 x 140

- Approach 5: 1x 155

Working sets:

2-3 sets of 5 reps with 165 kg

This doesn’t look so cool, but it allows you to increase your working weights by 2.5-5 kg per week. After some time you would manage 5 ideal reps with the same 1RM.

5. Excessive immersion in research VS practical experience

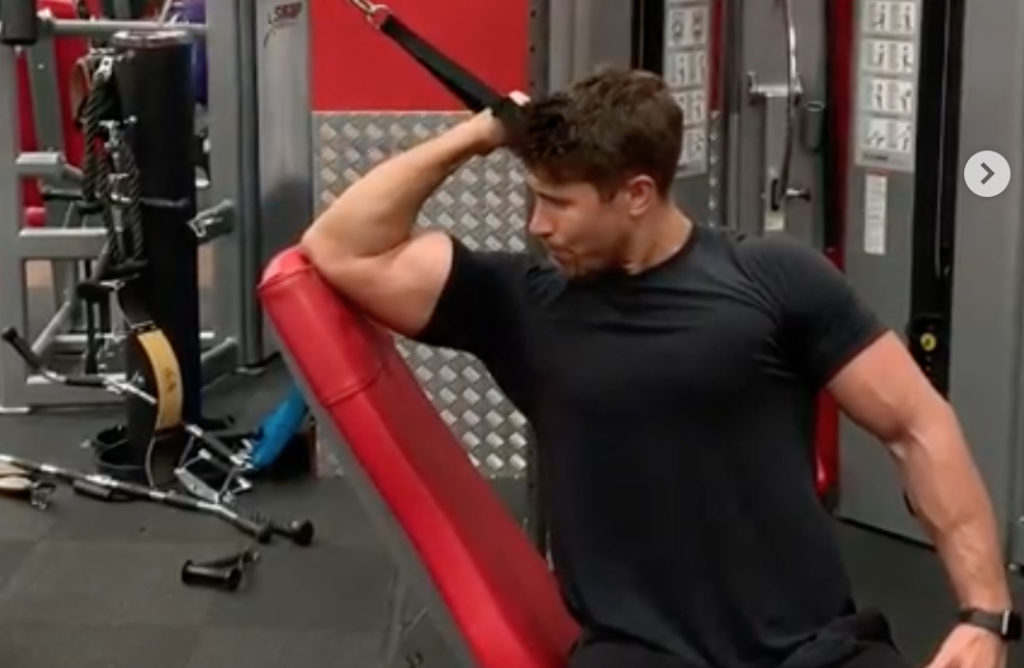

Lee Boyce, strength and conditioning specialist:

The scientific approach – when abused – has a couple of drawbacks:

1. one can search endlessly for the “optimal” methodology,

2. one may be confronted with “evidence-based” arguments against any exercise or technique.

Of course, people who have achieved outstanding success in strength sports also devote time to the study of their field. However, they spend an order of magnitude more time on the practical application of what they have learned, selecting exactly what suits them individually.

Reading research is useful, of course, but if you still weigh 60 kilos and pull 80, do not bombard the coach with questions about advanced periodisation, post-activation potentiality and so on. For now, you need to train easier but harder.

And, although not all fitness professionals are equally competent, try to find a good specialist in your gym. Yes, he will have to pay, but the payoff may be somewhat higher than reading scientific works in a free library.

6. Frequent changes of programmes VS permanence

Gareth Sapstead, fitness expert:

There’s too much information in this age, it’s overwhelming. The internet is full of programmes from trustworthy trainers. But if you jump from one to the other too often, they won’t do you any good. Choose one that suits your conditions (and leads to your goals), and devote enough time to it. Not for a day or a week, but as much as it requires, for example a whole month or even three.

Keep a training diary and write down all your observations and thoughts: what you like about the current programme, what you would like to change, how the body responds (changes in well-being) and, of course, what the results are. Study the programme, working through it fully and getting the most out of it, and then you’ll know what you need from the next one. Or maybe you’ll stay on the same one, making authorial changes to suit you.

7. What you want VS what you need

Andrew Coates, trainer and fitness podcaster:

Every now and then, each of us, in our eagerness to grab the bar sooner, miss an important little thing in the workout, such as joint mobility exercises. We come to the gym to lift a lot, so why waste time? But the thing is that if you do it all the time, you won’t make any progress in strength exercises either.

Before you jump into a squat frame or throw yourself on a bench, find time and energy for some light, but very useful preventive exercises, such as stretching a harness in front of you (for shoulder health). Of course, no one is forcing you to roll around on a massage roller for half an hour before the main part, but do your best to warm up and prepare your body for work. Take care of your joints and they’ll give you a harder, better workout in the long run.

And – since women already do it diligently – men, feel free to pump your glutes. You need to wake them up too, especially if you sit in the office all day and try to set records in the evenings in ‘big’ exercises.

8. Finding a magic wand VS getting the exercise right

Nick Tumminello, trainer of trainers (Zozhnik translated his excellent text “Myths about the perfect trainer”):

By ‘magic wand’ I mean some mystical technique that will give you everything at once: muscle mass, strength and power, as well as, of course, outstanding relief.

The problem is that it doesn’t exist. You can, however, devise an effective programme by finding the right exercises to suit your personal goals. With so many different programmes on offer these days, people get confused and don’t know what to take on.

Let’s untangle it by talking about three key principles of exercise selection:

- 1. Specificity. What you train will improve. For example, to develop power/speed you should include weightlifting exercises; to develop strength you should include slow lifts of higher weights. If your sport requires strengthening stabilisers of the body for example, work on the ‘cortex’ (read ’14 exercises for the whole cortex’ on Zohnik).

- 2. individuality. Don’t try to squeeze your native body into an uncomfortable movement pattern, adapt the movement to yourself. It is quite possible that some very effective exercises (techniques, programmes) will not suit you, because of your specific physique, injuries, motor limitations etc. Choose the exercises that you can do technically (and productively).

- 3. Regularity. Of course, it is useful to vary the exercises, but you still need to devote a certain amount of time to each one to get results. First establish a base by regularly practicing one set of simple movements, then you can add something new, more advanced.

9. Weight lifting VS Body movement

Susie Natel, personal trainer, powerlifter, psychologist:

One of the most common mistakes is to focus on how the weight moves rather than how the body performs the exercise.

Take, for example, the standing barbell: the barbell goes up and then goes down… only our body is not the barbell. Trying to lift up, we start pulling with our arms and/or overloading our back, working less with our legs.

Or squatting: the barbell goes down and then comes back up. But for this we have to remember that the pelvis is not only moved down, but also backwards; the knees are moved apart (but directed to the feet, ideally to the second toe – note Zohodnik). To return to the starting position, the pelvis must be moved forward and up diagonally, not just upwards.

Analyse all your exercises and focus on how your body needs to move. This way you will improve your technique, increase the activation of your working muscles and reduce the risk of injury.